Understanding the female hormonal cycle carries dual benefits, particularly in the context of endometriosis. This knowledge empowers women to become more attuned to their bodies and offers insights into how hormonal fluctuations impact various aspects of their lives. For instance, recognizing the distinct phases of the cycle can provide valuable information about when engaging in physical activities might be easier or when stress tolerance is higher.

In the case of endometriosis, a more in-depth understanding of the female hormonal cycle proves instrumental in comprehending the disease and its treatment. This is because the shifting hormonal landscape influences the behavior of endometriosis cells throughout the cycle.

It is worth noting that the explanation here pertains to the typical female cycle. In instances involving hormone therapy, the hormonal balance undergoes modifications.

To delineate the cycle, we will use consecutive numbering for the days, with the first day of menstruation marking the start of the cycle. On average, the menstrual cycle spans 28 days from this point. However, it is essential to recognize that for some women, the cycle might range from 26 to 35 days until the onset of the subsequent menstrual bleeding.

The menstrual cycle is typically divided into two phases, each characterized by distinct processes occurring in the uterus, ovaries, and hormonal balance.

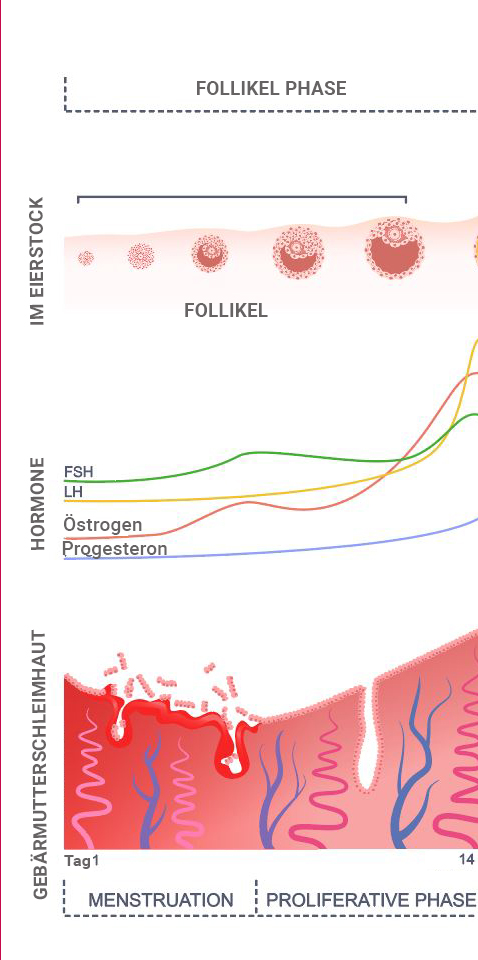

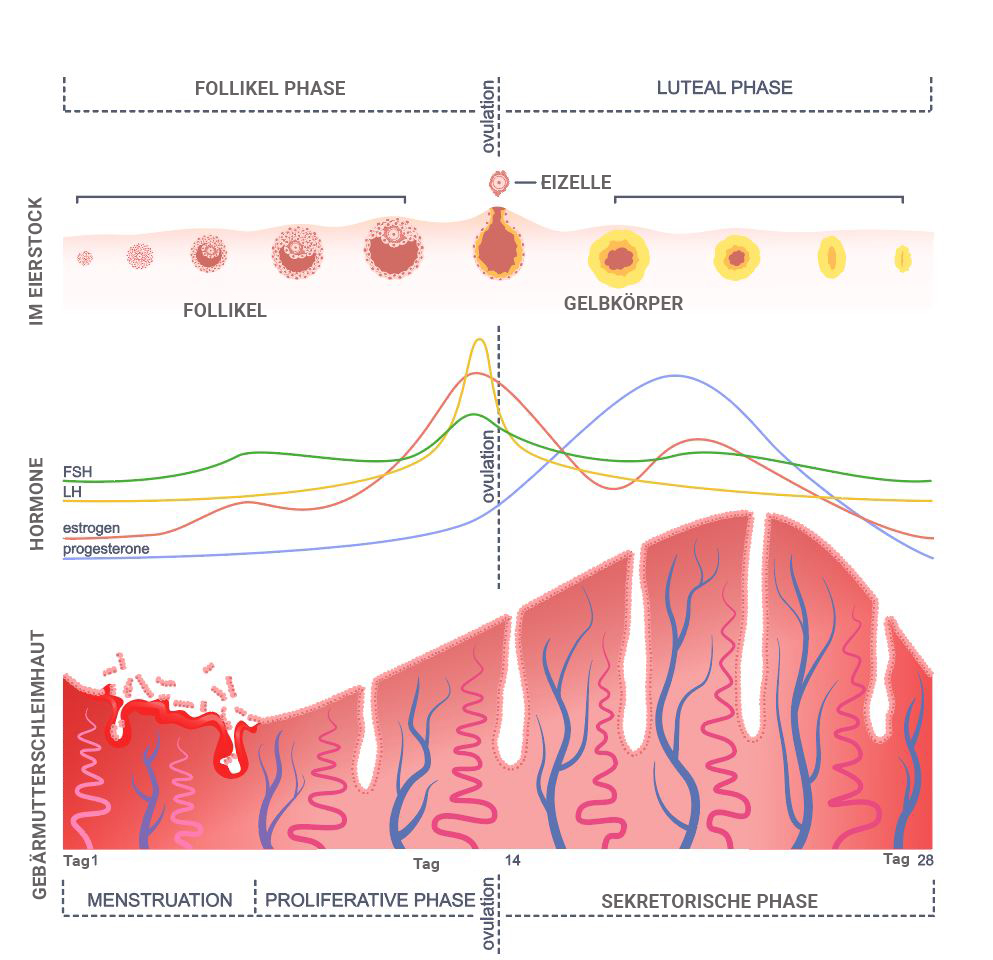

Day 1-14 – Follicular Phase

The first half of the cycle, spanning from day 1 to day 14, is called the follicular phase.

Ovary

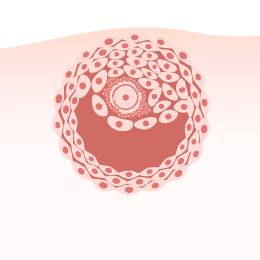

The name of this phase, the follicular phase, originates from the key events occurring in the ovary during this period. Within the ovary, eggs await their moment in the spotlight. Every month, multiple egg precursors undergo maturation within structures known as follicles, all under the control of the “follicle-stimulating hormone” (FSH) released by the pituitary gland. As part of this process, the follicles undergo enlargement.

These follicles

consist of the egg itself, surrounded by hormone-producing cells. Among these follicles, the one with the highest potential is selected and referred to as the dominant follicle. Within this follicle resides the cell that will eventually develop into the egg, which will be released from the ovary during ovulation and make its way into the fallopian tube.

Hormones

Within the follicles, there are specialized cells known as granulosa cells, and one of their functions is to produce estrogen. Consequently, during this phase, the ovary is actively generating the hormone. As the follicles grow, the number of granulosa cells increases, leading to a higher estrogen production. Its rise is gradual throughout this phase, with a more rapid increase toward the end, corresponding to the growth of the follicles.

This estrogen circulates into the bloodstream. Once its level reaches a specific threshold, it stimulates the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) within the brain’s pituitary gland. Subsequently, LH experiences a swift and substantial surge. This rapid and pronounced elevation of LH catalyzes the process of ovulation.

Uterus

Within the uterus, two consecutive processes unfold during this time frame. Given that the menstrual cycle initiates with the onset of menstruation, the initial process during the first 4–5 days is menstruation itself. This phase involves the shedding of the top layer of the uterine lining, known as the lamina functionalis. Subsequently, driven by the influence of estrogen produced during the follicular phase, this uterine layer is regenerated throughout the remainder. As a result, the period spanning day 4-15 of the follicular phase within the uterus is often referred to as the “growth phase” or “proliferation phase.”

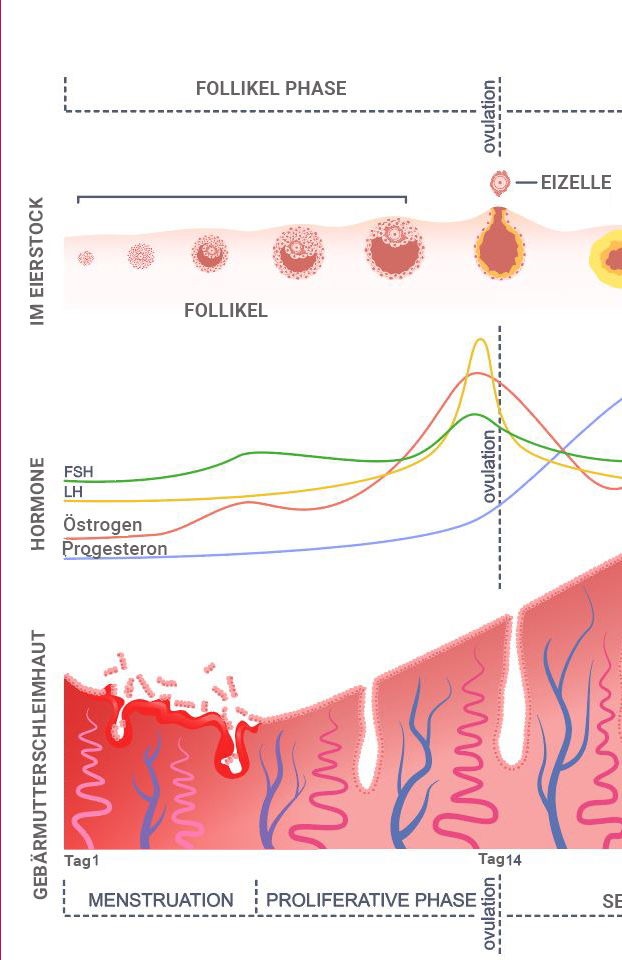

Ovulation

Ovulation typically occurs around the 14th day of the menstrual cycle. This pivotal event is initiated by the pronounced surge of the hormone LH, which, in turn, is prompted by the elevated estrogen production at the follicular phase’s conclusion. During the process of ovulation, the dominant follicle ruptures. This rupture results in the release of the contained egg, which is then transported into the fallopian tube. Meanwhile, the remaining portion of the follicle within the ovary transforms into a structure known as the corpus luteum.

Day 14-28 – The Luteal Phase

Ovary

Following ovulation, what remains of the follicle within the ovary transforms into what is known as the corpus luteum. This structure is so named because it takes on a yellowish appearance. Within the corpus luteum, specialized cells commence the production of progesterone. Consequently, progesterone is often referred to as the “corpus luteum hormone” due to its association with this ovarian structure.

Hormones

A significant presence of progesterone characterizes the luteal phase. This hormone is primarily produced by the corpus luteum, which continues to generate progesterone as long as it receives stimulation, either from the pituitary gland through LH (luteinizing hormone) or as a result of pregnancy. If pregnancy does not occur, progesterone production in the corpus luteum gradually diminishes.

Uterine lining

During the luteal phase, the presence of progesterone brings about changes in the uterine mucosa. The uterine lining, constructed in the menstrual cycle’s first half, transforms the second half. Under the influence of progesterone, the uterine cells develop in a manner conducive to providing an optimal environment for a potential pregnancy. This involves improved blood flow to the uterine lining and the production of a transparent secretion that supports the process. The uterine mucosa is sustained as long as there is sufficient progesterone.

However, if pregnancy fails to occur and the progesterone level in the bloodstream decreases, the blood supply to the upper layer of the uterine mucosa diminishes. Consequently, the top layer gradually undergoes cell death and is subsequently shed, marking the onset of menstruation on day 1 of the menstrual bleeding.

This cyclical process then commences anew.

Summary

During the first half of the cycle, follicles develop, comprising the egg cell and surrounding hormone-producing cells that generate estrogen. Elevated estrogen levels prompt the uterine lining to thicken.

Around the midpoint of the cycle, ovulation is triggered by a pituitary gland hormone, causing the egg to travel into the fallopian tube.

Subsequently, the remaining part of the follicle begins producing progesterone. The uterine lining receives ample blood supply thanks to progesterone, facilitating its continued growth and cell differentiation to fulfill its functions. The uterine lining receives reduced blood flow and nutrients if the progesterone level declines. As a result, the top layer dies off and is eventually shed, marking the start of a new cycle.

- Current Research on Endometriosis: An Interview with Deborah Bush - 6. February 2024

- Pain and Pain Management – Interview with Rehab Psychologist Teresa - 19. November 2023

- Physiotherapy for Endometriosis – Interview with Annika Cost – with Exercises - 19. November 2023