Development of Endometriosis: Background, Explanations, and Half-Truths

Endometriosis is a gynecological condition that impacts approximately 7 to 15 percent of women [1]. It falls under the category of estrogen-dependent inflammatory diseases, meaning it is an inflammatory condition regulated and influenced by the female sex hormone [2]. While its precise origins remain incompletely understood, 5 proposed explanatory models exist. Nevertheless, contemporary experts believe that the development and onset of endometriosis likely result from a combination of factors.

Background: The most Important Facts About Endometriosis

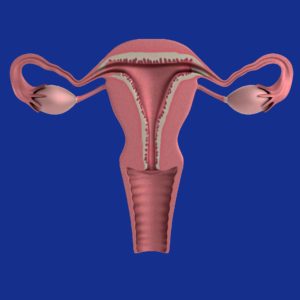

The term “endometriosis” is derived from the word “endometrium,” which refers to the mucous membrane exclusively present in the uterus [3]. In endometriosis, tissue with characteristics similar to that of the endometrium is found outside the uterus, leading to mild to severe symptoms in about two-thirds of affected women [1].

Endometriosis is characterized by endometrial-like cells outside the uterus, forming accumulations known as foci. These foci include glands, stromal cells, smooth muscle, nerve, lymphatic, and blood vessels. Therefore, it represents not individual cells but a relatively complete tissue with various cell types, a blood supply, and nerve cells [4]. The condition may manifest with varying degrees of symptoms or remain asymptomatic. It primarily affects women during their reproductive years, but in exceptional cases, it can also occur in prepubescent girls, postmenopausal women, and very rarely in men [4].

Good to Know!

In this article, you will discover insights into the following subjects:

- Understanding the Basics of Endometriosis

- Exploring Various Theories Surrounding the Development of Endometriosis

- Debunking Myths and Addressing Partial Truths Concerning Endometriosis Classification

Endometriosis was initially documented in 1690 by the German physician Daniel Schroen, who centered his doctoral thesis on “Disputatio inauguralis Medica de Ulceribus Uteri” (translating to Medical discussion on uterine ulcers). The term “endometriosis” was introduced by the American gynecologist John A. Sampson in 1920. In 1927, Sampson further developed his foundational theory known as transplantation theory.

Pathogenesis: What Are the Causes of Endometriosis?

Endometriosis remains a widespread gynecological condition, affecting approximately 2 million women in Germany alone. However, a definitive understanding of its development is still elusive [1,4].

There are currently five theoretical explanations [2], but none of these isolated theories can comprehensively account for the multifaceted nature of the condition. Consequently, contemporary experts contend that the development of endometriosis likely involves several factors.

Transplantation or Implantation Theory [2]

The transplantation theory, developed by John A. Sampson in 1927, is the oldest. It posits that menstrual blood, in addition to exiting through the vagina, also enters the abdominal cavity through the ovaries.

Although this phenomenon was not recognized in the 20th century, laparoscopies and abdominal endoscopies have revealed that between 76 and 90 percent of women experience the everyday occurrence known as retrograde menstruation. During menstruation, some menstrual blood flows into the abdominal cavity. However, it is essential to note that not all women who undergo retrograde menstruation develop endometriosis.

The implantation theory posits that the menstrual blood carrying vital endometrial cells is deposited in the abdominal cavity and becomes active there. There is scientific evidence supporting this aspect of the theory, suggesting that this may be how these cells find their way.

Despite these findings, the implantation theory falls short in explaining certain aspects of endometriosis:

- It does not explain why endometriosis affects only a fraction of women who experience retrograde menstruation.

- The theory does not account for endometriosis in rare cases among girls before their first menstruation, postmenopausal women, and even men.

- It also cannot elucidate how endometriosis lesions develop outside the abdominal cavity, such as in the lungs.

As a result, it is evident that while the implantation theory provides valuable insights, it does not offer a comprehensive explanation for the intricacies of endometriosis development.

Coelom Metaplasia Theory [2]

The coelom metaplasia theory proposed around 1919 by Robert Meyer suggests that endometriosis lesions developed from cells that initially lined the coelomic cavity during embryonic development. The coelomic cavity houses various organs, including the heart, lungs, digestive system, and specific urogenital organs.

Within the human body, cells exhibit diverse specializations, often stemming from standard precursor cells that subsequently transform to fulfill specific functions. This process can be likened to vocational training, where cells adapt in form, function, and appearance as needed. Notably, cells originating from the coelom are destined to develop into various organs, including the genital system, the peritoneum, and the digestive system.

The coelom metaplasia theory suggests that these cells, sharing a common origin, transform due to inflammatory or hormonal influences, ultimately becoming endometrial-like cells. This transformation process, known as metaplasia, involves existing cells evolving into cells resembling endometrium. Factors like estrogens and inflammatory processes can induce such differentiation.

This theory also offers insight into endometrial foci outside the abdominal cavity, particularly within the thoracic cavity or chest. Additionally, it explains the occurrence of endometriosis in women and girls both before and after their reproductive years and in men.

However, it is essential to consider certain aspects that may challenge this theory:

- Metaplasia tends to become more frequent with age, while endometriosis decreases.

- If one strictly adheres to this theory, endometriosis should be more prevalent in men, contradicting observed cases.

Induction Theory

The induction theory, introduced in 1955 by G. Levander and P. Normann, is an extension of the coelom metaplasia theory. According to this hypothesis, endometriosis lesions originate from undifferentiated cells, specifically stem cells, that persist in various tissues, even in adults. The transformation of these non-specific cells into cells resembling those of the endometrium is believed to be induced by biochemical or immunological factors originating from the endometrium.

Experiments involving rabbits have provided evidence supporting the validity of this theory. Moreover, it explains cases of endometriosis that occur independently of menstruation. However, it is worth noting that the tissue observed in these animal experiments lacked stromal components, unlike endometriosis foci in clinical cases. Consequently, the appearance of these foci in the experimental setting differs from clinical manifestations.

Embryonic Remnant Theory

The embryonic remnant theory, initially conceived in 1890 by von Recklinghausen and Russel, posits that endometriosis lesions originate from remnants of the so-called Müllerian ducts, tissues involved in developing reproductive organs. This theory explains the frequent occurrence of endometriosis in the Douglas space, a pocket-like depression located between the rectum and the uterus. Additionally, it elucidates the higher incidence of endometriosis in women with Müller’s anomalies, referring to malformations within the Müllerian ducts.

While there is some support for the embryonic remnant theory from studies involving embryonic autopsies, it fails to explain the presence of endometriosis lesions in distant locations.

Alternative theories, such as the development of endometriosis from other abdominal cells, undifferentiated progenitor cells (like stem cells), or remnants of genital development, may provide more comprehensive explanations for the condition.

Tissue-Injury and Repair Theory [9]

Contrary to long-held beliefs, the uterus possesses its peristalsis, a rhythmic muscular motion akin to the peristalsis in the intestine. This inherent uterine peristalsis is subject to continuous mechanical stresses, resulting in tiny injuries to the uterine tissue, termed microtraumas. These microtraumas predominantly occur during intense contractions that transpire during menstruation. The body constantly repairs these injuries, during which estrogens are released, subsequently triggering peristalsis.

Like variations in intestinal peristalsis among individuals, some women exhibit above-average uterine peristalsis. This heightened peristalsis leads to more microtrauma due to the release of estrogen during the repair process, perpetuating the cycle. Additionally, fewer pregnancies and a subsequent increase in menstrual periods contribute to additional micro-injuries.

As a result of estrogen secretion and inflammatory responses, these micro-injuries can incite alterations in the endometrial cells. These cells may then proliferate invasively into the uterine musculature and potentially migrate to the abdominal cavity.

This theory represents the most current understanding and is particularly effective in explaining adenomyosis. Nonetheless, it does not comprehensively explain all aspects of endometriosis.

Lymphatic and Vascular Dissemination Theory

The theory of lymphatic and vascular dissemination was independently developed by Halban in 1925 and Sampson in 1927. According to this theory, endometrial cells are transported through the bloodstream or lymphatic vessels to remote tissues, where they take root and give rise to endometriosis lesions. Recent discoveries, including identifying endometriosis cells in uterine veins and lymph nodes, have substantiated this theory.

While this theory explains the emergence of endometriosis lesions in distant tissues, it is not without its limitations. Notably, it fails to clarify why, in isolated instances, women lacking a uterus or men can also develop endometriosis.

Development of Endometriosis: Additional Factors

Physicians today believe that numerous factors must converge for endometriosis to develop. This is because none of the theories outlined earlier can, on its own, comprehensively explain the complexity of this condition. Among these contributing factors are:

- Iatrogenic Spread During Surgery [1]:

This pertains to the accidental dispersal of endometriosis cells to other body parts during uterine surgeries. While not an independent cause of endometriosis, it could elucidate why endometriosis lesions occasionally establish themselves in specific body regions. For example, scar endometriosis can arise following cesarean section surgery in the cesarean section scar.  Molecular Mechanisms [5]:

Molecular Mechanisms [5]:

Recent research has unveiled intricate molecular processes that result in the dysregulation or alteration of endometrial tissue. These alterations impact endometrial cells’ growth, invasiveness, and stem cell potential.- Hormonal changes [2]:

Studies have demonstrated that endometrial foci cells provoke an increase in estrogen levels. This estrogen surge acts as an amplifier in the development of endometriosis. Estrogen and progesterone levels are pivotal for developing and expanding endometriosis [10]. Typically, heightened estrogen levels coupled with reduced progesterone effect are contributing factors. - Genetics and Epigenetics [2]:

There is an elevated risk among the direct descendants of individuals with endometriosis also to develop the condition. This implies that genetic factors play a role in endometriosis development. However, external influences leading to genetic changes throughout an individual’s life also influence the emergence and progression of endometriosis.

Consequently, this is referred to as familial accumulation rather than direct heredity.

Myths and Misconceptions

Because the exact causes of endometriosis remain elusive, numerous myths and half-truths have emerged around this condition. These misconceptions can cause anxiety and may even lead individuals to pursue specific treatment hastily. Most myths contain some kernel of truth, but they are often presented out of context or misinterpreted. Here are some crucial facts about common myths and half-truths:

- You Can’t Develop Endometriosis Without a Uterus!

This statement is inaccurate. Statistically, individuals without a uterus (e.g., men, women with malformations, and those with a hysterectomy) are less likely to develop endometriosis. However, there are exceptional cases where endometriosis occurs in people without a uterus. Furthermore, endometriosis can reappear after a hysterectomy. Therefore, claims suggesting that endometriosis cannot exist without a uterus are incorrect. - Endometriosis Is Impossible After Menopause!

While endometriosis is most commonly diagnosed in women aged 25 and 35, there are exceptions, and it can be found in women after menopause [6]. The decrease in estrogen levels during menopause usually affects endometriosis. As a result, the condition often lessens or disappears during or after menopause [7].

However, it can still cause issues during menopause. Care must be taken when using estrogen-containing agents to alleviate menopausal symptoms since the drop in estrogen concentration is also responsible for reducing endometriosis symptoms, such as hot flashes. Surgical adhesions can persist during menopause. - Endometriosis Can Only Develop After the first Menstrual Period!

Endometriosis rarely occurs in girls before they enter the reproductive phase. Nevertheless, such cases exist [4]. - Endometriosis Is Exclusively a Female Condition!

Although endometriosis predominantly affects women, some men, particularly those undergoing high-dose estrogen treatment for prostate cancer, can develop the condition. - You Can’t Get Endometriosis While on Birth Control Pills! Birth control pills, or hormonal contraceptives, are used to manage endometriosis. Specific combined and progestogen-containing preparations can significantly alleviate endometriosis symptoms in numerous instances. However, taking birth control pills does not typically lead to a complete cure. Furthermore, treatment success usually persists while the pills are taken [8]. It is not a definitive solution or guarantee.

Summary:

Endometriosis, a condition widely considered a product of modern civilization due to its prevalence, remains a perplexing enigma for experts regarding its elusive causes. Various theories have been proposed, but each can only illuminate the condition’s specific facets. Consequently, contemporary experts believe that the development of endometriosis is likely influenced by a multitude of diverse factors, including:

- Hormonal Factors

- Immunological Processes

- Anatomical Conditions

- Genetic and Epigenetic factors

References

- https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Endometriose#Pathogenese (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.rosenfluh.ch/media/gynaekologie/2012/03/pathogenese.pdf (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.medizin.uni-tuebingen.de/de/das-klinikum/einrichtungen/kliniken/frauenklinik/endometriosezentrum/definition (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://opus4.kobv.de › Promotion_Silke_Landrith (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/418294-molecular-cues-into-the-pathogenesis-of-endometriosis/de (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0035-1558369 (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.deutschesgesundheitsportal.de/2021/07/06/endometriose-tritt-auch-nach-den-wechseljahren-auf/

original: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6473414/ - https://www.uk-erlangen.de/fileadmin/dateien/content_pool_dateien/infobroschueren/UEZ_endometriose_broschuere.pdf (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00404-009-1191-0

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41975-020-00168-7

- Endometriosis and Migraine: What is the Connection Between the Two Conditions? - 8. October 2023

- Endometriosis and Migraine: What is the Connection Between the Two Conditions? - 8. October 2023

- Can I Inherit Endometriosis? - 7. October 2023