Development of Endometriosis: Unraveling the Background, Clarifying Explanations, and Addressing Misconceptions

Endometriosis, impacting 7 to 15% of women [1], is among estrogen-dependent inflammatory conditions – linked to the female sex hormone [2]. Despite ongoing exploration, its exact causes remain elusive. While five explanatory pathways are under consideration, contemporary experts propose a multifactorial involvement in endometriosis’ emergence.

Insights into Endometriosis: Key Facts at a Glance

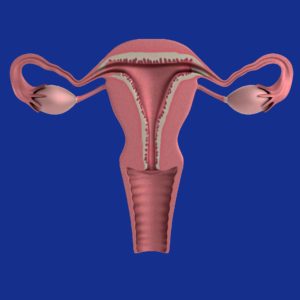

The term “endometriosis” finds its roots in “endometrium”, which refers to the uterine mucous membrane. This membrane is normally confined to the uterus [3]. However, in cases of endometriosis, tissue resembling the endometrium is found outside the uterus, triggering mild to severe symptoms in roughly two-thirds of affected women [1].

Endometriosis is marked by the presence of endometrial-like cells – cells mirroring those found in the uterine lining – outside the uterus. These cells congregate in clusters known as “foci”. Each focus comprises glands, stromal cells, and smooth muscle, interlaced with nerve, lymphatic, and blood vessels. Here, it is not just individual cells, but actual tissue hosting diverse cell types, blood supply, and nerve cells [4]. The condition can manifest with varying degrees of severity or remain asymptomatic. Its impact is predominantly felt by women during their reproductive years, yet in exceptional cases, it can surface in prepubescent girls, postmenopausal women, and, extremely rarely, in men [4].

In this article, you will find information on the following topics:

- Background knowledge about endometriosis

- Overview of the different theories on the development of endometriosis

- Myths and half-truths about endometriosis and how they should be classified

Endometriosis made its initial appearance in medical literature in 1690 when German physician Daniel Schroen presented his doctoral thesis titled “Disputatio inauguralis Medica de Ulceribus Uteri” (Medical Discussion about Ulcers in the Uterus). Nearly two centuries later, in 1920, American gynecologist John A. Sampson introduced the term “endometriosis” and, in 1927, formulated his pioneering transplantation theory to elucidate its origins.

Pathogenesis: What are the Causes of Endometriosis?

Despite its prevalence, impacting approximately two million women in Germany alone, the precise developmental trajectory of endometriosis remains elusive [1,4].

Presently, five distinct explanations shed light on its potential evolution [2]. However, these theories, taken individually, fall short of encompassing the diverse aspects of the condition. This complexity has led experts to surmise that the interplay of multiple factors contributes to the genesis of endometriosis.

Transplantation or Implantation theory [2]

Developed by John A. Sampson in 1927, the transplantation theory stands as the earliest perspective. It posits that menstrual blood beyond exiting through the vagina, partially traverses the ovaries, entering the abdominal cavity.

Modern insights, courtesy of laparoscopies (abdominal endoscopies), now reveal that 76 to 90 percent of women experience retrograde menstruation—where menstrual blood enters the abdominal cavity. This concept is commonplace, yet not all women undergoing this process manifest endometriosis.

This theory further hypothesizes that the menstrual blood within the abdominal cavity carries viable endometrial cells capable of implanting and thriving there. This notion has since found empirical support.

While this suggests a potential path for cell dissemination, the implantation theory leaves certain aspects unaddressed:

It fails to explain why endometriosis only affects a subset of women undergoing retrograde menstruation. It does not account for the occurrences of endometriosis in rare cases involving pre-menarche girls, postmenopausal women, and even men. In addition, it does not elucidate the development of endometriosis lesions outside the abdominal cavity, such as those found in the lungs.

Consequently, while the transplantation theory offers insight, it doesn’t encompass the entirety of endometriosis’ complexity.

Emergence from Resident Cells

Coelom Metaplasia Theory [2] – Origins from Kindred Cells

Devised around 1919 by Robert Meyer, the coelom metaplasia theory asserts that endometriosis lesions originate from cells that originally lined the coelomic cavity during embryonic development. This cavity houses vital organs like the heart, lungs, digestive system, and select urogenital organs.

Cell specialization varies widely throughout the body. Many cells stem from common precursor cells, which then undergo differentiation to assume their ultimate functions—akin to vocational training, altering cells’ form, function, and appearance to suit specific roles. Coelomic cells give rise to genital organ cells, peritoneal cells, and even digestive system cells.

The theory proposes that these cells, sharing a common origin, undergo a transformation via inflammatory or hormonal influences, becoming endometrial-like cells. This phenomenon, known as metaplasia by experts, is an expert-defined process. Existing cells shift to resemble endometrial cells, often spurred by hormone influence, such as estrogens, or inflammatory processes.

This theory extends to elucidate the presence of endometrial foci beyond the abdominal cavity, particularly within the thoracic cavity. Furthermore, it accounts for endometriosis occurrences before or after the reproductive phase, in both genders.

Challenges to this theory include:

- Metaplasia increasingly occurs with age, yet endometriosis prevalence diminishes over time.

- If the theory held true, endometriosis should be more prevalent in men, which is not the case.

Induction Theory

A progression from the coelom metaplasia theory, the induction theory emerged in 1955 through the work of G. Levander and P. Normann. This theory postulates that endometriosis lesions stem from undifferentiated cells, or in other words, stem cells. Even in adults, some tissues still house these versatile cells. The transformation of these unspecialized cells into endometrium-like cells, according to this theory, is triggered by biochemical or immunological factors originating from the endometrium.

Support for the induction theory has surfaced through animal experiments involving rabbits. These experiments indicate its validity. Furthermore, this theory offers an explanation for the occurrence of endometriosis independent of menstruation. However, these animal experiments failed to identify stromal components in the detected tissue. In contrast, endometriosis foci comprise stromal cells. Consequently, the foci observed in the experiments diverged somewhat from the clinical counterparts.

Embryonic Remnant Theory

The embryonic remnant theory, dating back to 1890 with contributions from von Recklinghausen and Russel, posits that endometriosis lesions stem from remnants of the Müllerian ducts – a tissue pivotal in the development of reproductive organs. This theory provides insight into why endometriosis often occurs in the Douglas space, a pocket-like depression in the peritoneum between the uterus and rectum. Additionally, it accounts for the prevalence of endometriosis in women with Müller’s anomalies – malformations in the Müllerian duct area.

While studies on embryos, including post-miscarriage or abortion autopsies, lend support to the embryonic remnant theory, it fails to account for distant endometriosis lesions.

In search of a comprehensive explanation, theories suggesting development from other abdominal cells, undifferentiated progenitor cells (like stem cells), or remnants of genital development—such as supernumerary cells—have been put forward.

Tissue-Injury and Repair Theory [9]

Contrary to long-held assumptions, the uterus possesses its own peristalsis – rhythmic muscular movement. Analogous to the intestine, the uterus faces persistent mechanical stress, inducing tiny tissue injuries referred to as microtraumas. These microtraumas primarily emerge during robust contractions in menstruation. The reparative mechanisms promptly attend to these injuries, triggering the release of estrogen, further activating peristalsis during the repair process.

Much like individuals exhibiting heightened intestinal peristalsis, some women exhibit above-average uterine peristalsis. Consequently, an escalated cycle of microtrauma ensues, stimulating increased uterine peristalsis through estrogen release in repair mode, perpetuating microtrauma. Furthermore, reduced pregnancies and an elevated number of menstrual cycles are believed to contribute to heightened micro-injury occurrences.

With estrogen secretion and inflammatory reactions at play, multiple micro-injuries can cause modifications in endometrial cells. These cells then invasively grow into the uterine musculature and may even migrate within the abdomen due to these changes.

While this, most current theory, adeptly accounts for adenomyosis, it is still unable to comprehensively explain all aspects of endometriosis.

Lymphatic and Vascular Dissemination Theory

Originating in 1925 by Halban and expanded by Sampson in 1927, the lymphatic and vascular dissemination theory posits that endometrial cells embark on journeys via blood or lymphatic pathways to distant tissues. Upon arrival, these cells take root, giving rise to endometriosis lesions. Recent evidence of endometriosis cells in uterine veins and lymph nodes lends credence to this theory.

This theory effectively accounts for the development of endometriosis lesions in remote tissues. Yet, it has its limitations: it cannot elucidate the occurrence of endometriosis in cases involving women without a uterus or in men.

Endometriosis Development: Exploring Additional Contributing Factors

As previously mentioned, the current consensus among medical professionals is that a convergence of numerous factors is necessary for the inception of endometriosis. The theories examined earlier, while shedding light on various aspects, fail to comprehensively account for the full spectrum of this condition’s development. Notable among these additional factors are:

- Iatrogenic Carryover During Surgery [1]

This pertains to the spread of endometriosis cells to other body regions during surgeries involving the uterine area. While this doesn’t directly explain the condition’s development, it may elucidate the reason endometriosis lesions manifest in specific body regions. For instance, scar endometriosis following cesarean section surgery within the cesarean section scar.  Molecular Mechanisms [5]

Molecular Mechanisms [5]

Recent research delves into molecular-level mechanisms that result in the deregulation or alteration of endometrial tissue. This deregulation influences the growth, invasiveness, and stem cell capabilities of endometrial cells.- Hormonal Changes [2]

Endometrial foci cells have been linked to elevated estrogen concentrations, intensifying the advancement of endometriosis. Hormonal levels of estrogen and progesterone play pivotal roles in its development and growth [10], typically involving escalated estrogen concentration and reduced progesterone effects. - Genetics and Epigenetics [2] Offspring of endometriosis sufferers exhibit an increased risk of developing endometriosis, suggesting a genetic role. However, the interplay of external factors inducing gene alterations over a lifespan also influences endometriosis’ course and development.

This implies familial predisposition rather than direct heredity.

Myths and Half-Truths

Amid the ambiguities surrounding the etiology of endometriosis, numerous myths and partial truths pervade discussions on the topic. These misconceptions can mislead and potentially hasten individuals towards misguided therapeutic paths. In many instances, these myths harbor a kernel of truth, but they are often employed in inappropriate contexts or misconstrued. Here you will find the key insights into prevalent myths and half-truths:

- You can’t get endometriosis without a uterus!

This statement is inaccurate. While those without a uterus—men, women with malformations, or individuals who’ve undergone hysterectomies—are statistically less prone to endometriosis, exceptional cases do exist where it develops in those without a uterus. Moreover, endometriosis can persist post-hysterectomy. Claims that endometriosis cannot occur without a uterus are incorrect. - You can’t have endometriosis after menopause!

Most commonly identified in women aged 25 to 35, endometriosis can be identified in women post-menopause in exceptional scenarios [6]. During menopause, estrogen levels decline, affecting endometriosis. While the condition often diminishes or vanishes during or after menopause, it can still pose problems. [7].

Caution is advised with estrogen-containing agents to alleviate menopausal symptoms, as the estrogen decrease contributing to symptom relief (e.g., hot flashes), also underlies endometriosis alleviation. And adhesions from surgeries can persist even during menopause.

However, the silver lining lies in the fact that, for the majority, endometriosis tends to ameliorate significantly during this phase! - Endometriosis can occur only after the first menstrual bleeding!

Endometriosis rarely arises in girls prior to reproductive age, though instances do exist [4]. - Endometriosis is a female-only disease!

Predominantly affecting women, endometriosis has also been observed in a limited number of males. This typically emerges in males undergoing high-dose estrogen treatment as part of prostate cancer therapy. - You can’t get endometriosis with the “pill”! While hormonal contraceptives, including certain combined and progestogen formulations, are indeed harnessed to mitigate endometriosis symptoms, taking the pill seldom leads to complete remission. Symptom relief, typically tied to contraceptive use, rarely extends beyond its consumption [8].

In Summary:

Endometriosis, an affliction that sometimes garners the moniker “disease of civilization” due to its ubiquity, remains a complex enigma regarding its origins. While diverse theories abound, none can entirely encapsulate its multifaceted nature. Hence, experts posit that a medley of factors contributes to endometriosis’ onset. These include:

- Hormonal dynamics

- Immunological processes

- Anatomical variables

- Genetic and epigenetic influences

References

- https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Endometriose#Pathogenese (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.rosenfluh.ch/media/gynaekologie/2012/03/pathogenese.pdf (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.medizin.uni-tuebingen.de/de/das-klinikum/einrichtungen/kliniken/frauenklinik/endometriosezentrum/definition (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://opus4.kobv.de › Promotion_Silke_Landrith (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/418294-molecular-cues-into-the-pathogenesis-of-endometriosis/de (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0035-1558369 (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://www.deutschesgesundheitsportal.de/2021/07/06/endometriose-tritt-auch-nach-den-wechseljahren-auf/

original: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6473414/ - https://www.uk-erlangen.de/fileadmin/dateien/content_pool_dateien/infobroschueren/UEZ_endometriose_broschuere.pdf (retrieved 08/16/2021)

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00404-009-1191-0

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41975-020-00168-7

- Endometriosis and Migraine: What is the Connection Between the Two Conditions? - 8. October 2023

- Endometriosis and Migraine: What is the Connection Between the Two Conditions? - 8. October 2023

- Can I Inherit Endometriosis? - 7. October 2023