Adenomyosis: Causes, Diagnosis and Therapy as well as Differentiation from Endometriosis

Adenomyosis: A condition once considered a subtype of endometriosis, adenomyosis involves changes in the muscular layer of the uterus, leading to pain and potential fertility issues, including miscarriage. Like endometriosis, its causes remain unclear, making prevention impossible.

Modern medicine offers various therapeutic options, including medicinal and surgical interventions. Contrary to previous assumptions, adenomyosis is not limited to women in the later stages of reproductive life or post-menopause; it can also affect younger women [1].

Understanding Adenomyosis: A Definition

Adenomyosis, historically categorized as a subtype of endometriosis, is a gynecological condition characterized by the infiltration of endometrial-like tissue into the muscular layer of the uterus. These infiltrations comprise both glands and stroma. Additionally, adenomyosis may entail an overall enlargement of the uterus and disturbances in the junctional zone between the uterine muscle and the endometrium. Adenomyosis can manifest as a localized condition, similar to fibroids, or diffuse throughout the uterine muscle. There is also a mixed form wherein diffuse and localized infiltrations are present [2, 3].

Accurate prevalence figures for adenomyosis remain elusive, with reported estimates ranging from 5 to 70 percent. Several factors contribute to this variability: the challenges in distinguishing adenomyosis from endometriosis and, in some instances, from fibroids (benign growths). Furthermore, these statistics are often derived from post-hysterectomy examinations, primarily conducted after the reproductive phase and typically in severe symptoms [4].

Adenomyosis and Endometriosis

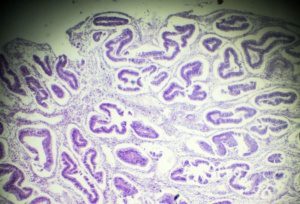

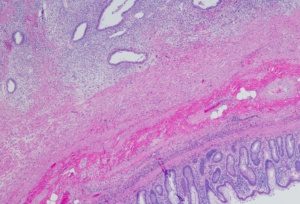

A Comparison under the Microscope

Adenomyosis:

Endometriosis:

Symptoms: Understanding the Effects of Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis often manifests as chronic lower abdominal pain, primarily attributed to the growth of endometrial-like tissue within the uterine muscle. Alongside this, individuals may experience pain during menstruation, discomfort during sexual intercourse, and various bleeding irregularities. In some cases, women with adenomyosis encounter what is known as retrograde menstruation. This not only results in abdominal bleeding during the menstrual period but can also impede an egg’s typical path, favoring transport into the abdomen rather than the uterus due to fallopian tube movement [9]. Consequently, adenomyosis can contribute to infertility and an increased risk of miscarriages due to mucosal changes [5].

However, it is essential to note that women with adenomyosis can still become pregnant. According to current research, approximately 30 percent of affected women experience minimal or no symptoms [6].

Differentiation: Unpacking the Similarities and Distinctions Between Endometriosis and Adenomyosis

‘Endometriosis’ derives from ‘endometrium,’ the scientific name for the uterine lining. In endometriosis, clusters of cells known as ‘endometriosis foci’ form outside the uterus and resemble the uterine lining. These foci consist of glands, stromal cells, and smooth muscle supported by nerves, lymphatic vessels, and blood vessels [7].

Endometriosis typically gives rise to chronic abdominal pain, often exacerbated during menstruation, as well as bleeding abnormalities, pain during sexual intercourse, and difficulties conceiving. These symptoms closely parallel those associated with adenomyosis. Given the substantial symptom overlap and limited diagnostic means, adenomyosis was historically considered a subtype of endometriosis, differentiated primarily by its location:

- Endometriosis within the uterus is called ‘endometriosis genitalis interna,’ essentially adenomyosis.

- Endometriosis outside the uterus is called ‘endometriosis genitalis externa.’

- If endometriosis appears beyond the pelvic region, it is classified as ‘endometriosis extragenitalis.’

Despite the shared clinical features, extensive research has unveiled numerous molecular, epigenetic, and risk factor disparities between the two conditions. Consequently, adenomyosis is no longer classified as a subtype of endometriosis. Although the term ‘endometriosis genitalis interna’ persists in some references [8], it has been largely abandoned in the contemporary medical literature.

However, current knowledge indicates that up to 22 percent of affected women contend with endometriosis and adenomyosis. The extent to which these conditions influence one another, share common causes, or even precipitate each other remains an area of ongoing investigation [1].

Causes: Unraveling the Development of Adenomyosis

The precise factors that trigger the development of adenomyosis remain a subject of ongoing research, with several theories and risk factors identified. These are outlined below:

One theory suggests that mucosal cells from the uterine lining migrate into the muscular layer when the ‘junctional zone,’ an intermediate layer between the endometrium and the muscular layer, is disturbed. Such disruption may occur due to surgery or scraping, often associated with procedures like abortions or miscarriages [10].

Another theory posits that degenerated tissue or stem cells within the muscle layer of the uterine wall play a role in the development of adenomyosis [11].

A recent theory proposes that strong uterine contractions may cause micro-tears in the layer separating the mucosa from the muscle. These injuries subsequently stimulate an increased release of estrogen and permit the infiltration of cells into the muscular layer. This phenomenon, referred to as ’tissue-injury-and-repair’ (TIAR), is recognized in adenomyosis but, like other theories, has yet to be definitively proven.

Several risk factors have been associated with the development of adenomyosis, including:

- Uterine surgeries

- Multiple pregnancies

- Advanced age

- Early onset of first menstruation (at age 10 or younger)

- Short menstrual cycles (24 days or less)

- Obesity [12]

Diagnosis: How is Adenomyosis Diagnosed?

Formally, the definitive diagnosis of adenomyosis relies on histology, which entails examining a tissue sample [9]. Nevertheless, non-invasive diagnostic methods are now in use.

Non-invasive diagnostic techniques include:

- Sonography, utilizing both conventional 2D ultrasound and more recent elastography (3D ultrasound), with both procedures employing a vaginal probe. While 2D ultrasound is the typical choice in clinical settings, both techniques gauge the thickness and structure of specific areas, with 3D ultrasound offering an added dimension by assessing tissue elasticity. This combination helps enhance the assessment for potential adenomyosis changes [13]. As per the guidelines for diagnosing and treating endometriosis and adenomyosis, sonography is the initial step in confirming a suspected ‘adenomyosis’ diagnosis.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), another imaging technique, produces results comparable to sonography in assessing the junctional zone’s thickness and structure. However, MRI results tend to be more reproducible. While MRI is considered a second-line diagnostic method in the guideline program, it plays a pivotal role when performed by an experienced radiologist. It aids in distinguishing fibroids and is essential for pre-surgical assessments in fertility patients.

Invasive diagnostic methods involve

- Hysteroscopy, a direct examination of the uterine interior utilizing an endoscope inserted through the vaginal route. While adenomyosis cannot be directly visualized during this procedure, specific indicators, such as severely dilated vessels, may suggest its presence. Hysteroscopy can also facilitate tissue sampling for subsequent examination. However, these samples often yield limited conclusive results as they are typically obtained from a superficial layer.

- Laparoscopy involves an endoscope insertion into the abdomen via a small incision, with additional instruments introduced through a second small incision. Laparoscopy estimates the uterus’s size and position, offering insights into the potential existence of adenomyosis, as an enlarged uterus may be indicative. However, locating adenomyosis externally during laparoscopy can be challenging, making tissue sampling difficult. As a result, biopsies are rarely conducted outside therapeutic surgery, as per the guidelines.

Treatment: Addressing Adenomyosis

The causal factors behind adenomyosis remain elusive, thus making it challenging to provide a definitive cure. Nonetheless, diverse treatment approaches are available, encompassing pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical methods. Treatment choice depends on individual factors, with particular consideration given to the patient’s age and fertility desires.

Pharmaceutical Treatment Approaches for Adenomyosis

Given the close relationship between adenomyosis and endometriosis, pharmaceutical treatment strategies often draw from the experience in endometriosis therapy. However, it is essential to note that all drug treatments exhibit their effects only as long as the treatment regimen continues. Many women may not respond to these drug treatments or continue to grapple with residual symptoms.

Key pharmaceutical therapy concepts include:

- Hormonal Treatment Approaches:

A range of substances can be employed in hormonal therapy, encompassing progestins, GnRH analogs, aromatase inhibitors, and levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (IUDs). These hormonal therapeutics can be administered through various methods, such as localized applications (e.g., hormonal coils) or injections into subcutaneous or intramuscular tissue. - Non-Hormonal Treatment Approaches:

Drawing from experience in endometriosis treatment, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and painkillers are utilized because pain is a predominant symptom in adenomyosis. - Integrative Medicinal Therapy Approaches:

As per the guideline program, treatment approaches from traditional Chinese medicine, including using San Jie Zhen Tong capsules, have not yet demonstrated apparent positive effects.

Surgical Treatment Options for Adenomyosis

The main surgical treatment options are:

- Hysterectomy:

Hysterectomy entails completely removing the uterus or specific uterine portions; while adenomyosis growths are confined to the uterus, pain relief may not always be guaranteed. Hysterectomy can introduce other complications and is unsuitable for women wishing to conceive. - Resection:

In resection, the adenomyosis-affected parts of the uterus are removed during a single procedure. The uterus as a whole organ remains intact, and post-operative recommendations may be included. After the operation, individual recommendations usually apply to births, e.g., the performance of a planned cesarean section. - Embolization:

Embolization or endometrial ablation involves removing or cutting growths from their nutrient supply via blood vessels. These procedures are typically reserved for women who have completed their family planning or do not intend to have children. As per the guideline program, these procedures should be exclusively administered within the context of clinical studies.

Given the prolonged presence of pain associated with adenomyosis, women should consider multimodal pain management strategies to enhance their overall quality of life.

Summary:

Adenomyosis uteri, commonly referred to as adenomyosis, is a condition affecting the uterus, characterized by the infiltration of endometrial-like tissue into the uterine muscular layer. These tissue growths resemble those seen in endometriosis outside the uterus. The symptoms associated with adenomyosis closely mirror those of endometriosis, including abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, and subfertility.

While adenomyosis was historically considered a subtype of endometriosis, it is now recognized as a distinct medical condition. Nonetheless, a strong correlation exists between adenomyosis and endometriosis, with many individuals experiencing both conditions concurrently. The precise nature of this connection remains under ongoing investigation.

Treatment for adenomyosis varies depending on individual findings and circumstances, encompassing medical and surgical approaches. Additionally, multimodal pain therapy measures are often recommended to enhance the overall quality of life.

If you are grappling with adenomyosis and are curious about the suitability of the Endo-App for your needs, the answer is a resounding ‘Yes!’ Download the Endo-App to access valuable insights from experts in the field.

References

- Gynecology 1/2018; The Adenomyosis, Update 2018; Retrieved from: https://www.rosenfluh.ch/media/gynaekologie/2018/01/Die-Adenomyose.pdf

- Farquhar C, Brosens I.: Medical and surgical management of adenomyosis. Best practice & research Clin Obstet & Gynaecol 2006; 20(4): 603-616.

- Bergeron C, Amant F, Ferenczy A.: Pathology and physiopathology of adenomyosis. Best practice & research Clin Obstet & Gynaeco. 2006; 20(4): 511-521

- Uduwela AS, Perera MA, Aiqing L, Fraser IS: Endometrial-myometrial interface: relationship to adenomyosis and changes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000; 55(6): 390-400.

- Does the presence of adenomyosis affect reproductive outcomes in IVF cycles? A retrospective analysis of 973 patients; via: https://www.deutschesgesundheitsportal.de/2021/07/06/mehr-komplikationen-in-der-schwangerschaft-bei-adenomyose/

- Peric H, Fraser IS: The symptomatology of adenomyosis. Best pract & research Clin Obstet & Gynaecol 2006; 20(4): 547-555.

- Andreas D. Ebert; Endometriosis, A guide to practice; De Gruyter.

- Benagiano G, Brosens I, Habiba M.: Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014; 20(3): 386-402.

- https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-045l_S2k_Diagnostik_Therapie_Endometriose_2020-09.pdf; from page 80

- Uduwela AS, Perera MA, Aiqing L, Fraser IS: Endometrial-myometrial interface: relationship to adenomyosis and changes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000; 55(6): 390-400.

- Vannuccini S, Tosti C, Carmona F, et al: Pathogenesis of adenomyosis: an update on molecular mechanisms.

Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2017Parrott E, Butterworth M, Green A, White IN, Greaves P.: Adenomyosis – a result of disordered stromal differentiation. American J Patho 2001; 159(2): 623-630.

Benagiano G, Habiba M, Brosens I.: The pathophysiology of uterine adenomyosis: an update. Fertility and sterility. 2012; 98(3): 572-579.

Hufnagel D, Li F, Cosar E, Krikun G, Taylor HS.: The Role of Stem Cells in the Etiology and Pathophysiology of Endometriosis. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 2015; 33(5): 333-340.

- https://www.springermedizin.de/emedpedia/reproduktionsmedizin/adenomyose?epediaDoi=10.1007%2F978-3-662-55601-6_36

- https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0035-1553266

- Endometriosis and Migraine: What is the Connection Between the Two Conditions? - 8. October 2023

- Endometriosis and Migraine: What is the Connection Between the Two Conditions? - 8. October 2023

- Can I Inherit Endometriosis? - 7. October 2023